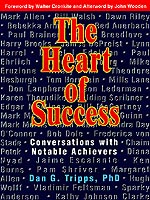

Heart of Success

Conversations With Notable Achievers

By Dan G Tripps

January 2001

Foreword by Walter Cronkite

Afterword by John Wooden

ISBN: 1-891696-12-2

298 pages Illustrated

$22.50 Paper Original

Review

from Publishers Weekly

"Former presidential candidate Bob Dole and songwriter/singer

Roger McGuinn of the Byrds are only a couple of the admirable figures featured

in Dan G. Tripps's The Heart of Success: Conversations with Notable

Achievers, with a foreword by Walter Cronkite and an afterword by John

Wooden. As a professor who teaches about achievement, Tripps illustrates the

fundamental principles of discipline, perseverance and leadership through

a discussion with legendary boxing referee Mills Lane (better known as the

honorable Judge Mills Lane) and a moving description of Rebekka Armstrong's

career shift from Playboy Playmate to AIDS activist. Although some "conversations"

may read more like brief bios, the range and depth of these profiles should

appeal to go-getters burning to unearth the secret of success."

Other Reviews

"The Heart of Success gets to the heart of the matter in revealing

what molds achievers and propels them to the highest levels of accomplishment."

John H. Johnson, Publisher, Chairman and CEO of Johnson Publishing

Company, Inc.

(Publisher of Ebony magazine)

"Dr. Tripps offers a rare insight into people and an ability to listen

to what they have to say. One feels intimately connected to leaders of our

time who otherwise seem so untouchable."

Edna Landau, Managing Director, IMG Artists

"The pursuit of success can be as elusive as trying to rope a cloud.

But if we throw that rope out enough times, sometimes it can happen. Dan G.

Tripps provides a kaleidoscope of accomplished 'ropers' who share their vision

in straight talk to the reader."

Dan Ewald, author and former Public Relations Director, Detroit Tigers

Here is a unique collection of conversations with 40 prominent individuals

in business, government, science, education, sports, and the arts who discuss

the essence of success. Gleaned from hours of taped interviews, the author

presents profiles of a diverse group of successful men and women, young and

old, who provide anecdotes from their lives and experiences. The inspirational

comments reveal the people behind their accomplishments and enable readers

to understand the personal side of achievement, empowering them as they seek

professional success and guiding them as they live their lives. Perfect reading

for executives, administrators, educators, mentors, coaches, performers, and

young people.

THE AUTHOR holds degrees from the University of Oregon, Stanford University and San Francisco State University. He has published dozens of articles on the physiological and psychological aspects of sports, and is at work on a book for Simon & Schuster about the history of the World Series. He has worked for the Olympics, Goodwill Games, and serves as a consultant to major corporations, such as Nike Inc. and Wells Fargo Bank.

EXCEPTS FROM THE BOOK

The Heart of Success Excerpts from Chapter One, The Lure of

Success

Whether in first grade or graduate school, in my office or at a pub, it was

clear to me that chanting the litany of achievers or trying to become one

of them was part of an American ritual. So, like many others, I joined the

choir. I pursued the dream of achievement as a performer, as an athlete in

high school and college. I shaped the dream of achievement as a mentor, as

a coach for dozens of All-American, professional and Olympic competitors.

At every step of the journey, I was surrounded by people devoted to reaching

their dreams. I was also engulfed by three nagging questions: Why did some

make it while others did not? Was it worth it when they got there? What was

success after all?

Now, as a professor teaching about achievement, it seemed like the right time

to go looking for answers. So, I did just that. In the pages that follow,

you will find profiles of 40 of those I met. They share personal reflections

of their careers and their lives. Their remarks are often inspirational and

reveal the people behind the accomplishments. In the first eight chapters,

they discuss critical factors common to their achievements: focused will,

self-discipline, intuition, hard work, overcoming obstacles, going the distance,

taking risks, and working with others. In the closing chapters they offer

two powerful perspectives on the real merits of achievement: understanding

self and making a difference for others. All together, the ten collections

serve to define the heart of success. A book on extraordinary achievement

built on interviews could be challenged with regard to the individuals or

the accomplishments selected.

While extraordinary achievers and extraordinary achievements have been the

consummate symbols of success in America, America is a complex and diverse

society, and what Americans deem to be extraordinary has taken many different

forms. But I truly believe the individuals interviewed constitute a representative

sample of American achievement. Let me explain my thinking and introduce the

individuals. Adventurers have always been viewed as extraordinary achievers.

In the early years of the nation, it was frontiersmen like Davy Crockett,

pioneers like Calamity Jane, and explorers like Robert Peary. At the dawning

of the 20th Century, extraordinary achievement for the adventurer was conquest

of the sky. The Wright Brothers soared in flight. Chuck Yeager broke the sound

barrier. John Glenn ventured into outer space. Today, with few places to explore,

all that is left of the adventurer are the daredevils who claim attention

through courageous feats reported by the media; sailor Karen Thorndike, land-speed

fanatic Craig Breedlove, and mountaineer Tom Hornbein, all profiled in this

book, are among them. Capitalists have often been among those deemed successful.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries a host of industrialists succeeded

in ways so extraordinary that measured in dollars their achievements remain

hard to comprehend. Nearly all were poor. Few were formally educated. They

earned the admiration of the nation for rising up and making it on their own

as did J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, and John D. Rockefeller among many.

Although most American CEO's are among the most wealthy people on the planet,

they are not given the esteem of their predecessors. While America is a country

where the love of money is epidemic, it is the manner in which it is obtained

that matters.

Success is characterized by entrepreneurs who have amazing instinct, like

IMG President, Mark McCormack, are courageous enough to take risks akin to

desktop publishing inventor, Paul Brainerd, or who lead a small band of comrades

from vision to victory, similar to public relations founder, Daniel Edelman.

Politics was an achievement area that regularly produced icons of success

across the years from George Washington to Abraham Lincoln to Franklin Roosevelt

to John Kennedy. But the advent of television and the quasi-tabloid approach

to investigative journalism have made politics a quagmire, mudding the waters

by creating a skeptical, if not cynical, public. The result is that image

has become the single most important criterion for political success. Just

listen to former presidential candidate, Bob Dole, who talks about it in the

pages ahead. Ironically, the Justices of the Supreme Court have no regard

for image and shun personal publicity and media coverage. Of course, that

may explain why no one you know can name all nine and why law today is short

on John Marshalls or notable figures at all, unless the profile of Sandra

Day O'Connor presents her as an exception.

Arguably, the military has produced more esteemed Americans than any other

institution. Army Generals George Patton and Douglas MacArthur, Navy Admiral

William Hasley, Air Force General William Mitchell, and Marine Colonel Gregory

Boyington earned their honors as America fought the Mexican War, two World

Wars, and Korea. But the attack on the morality and efficacy of the U.S. military

that began during Vietnam altered our traditional high regard for the military.

Subsequent incidents such as the Iran hostage rescue, Lebannon peacekeeping

force, and complicated operations in Panama, Iraq, Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia,

and Kosovo explain why few military heroes have emerged since and why the

nation views POWs as the real heroes of the war. It also explains why the

nation looks to officers of principle and dignity, like General Harry Brooks,

as the real leaders of the armed forces. Scientists have occasionally been

included in the pantheon of success. Thomas Edison, Albert Einstein, and Jonas

Salk are as familiar as Erector sets. But like the toy, they are from another

time. Today, despite having unlocked the secrets of DNA, James Watson and

Francis Crick are practically anonymous. So are those who give life to the

dying, like heart transplant surgeon Margaret Allen, and Belding Scribner,

whose work paved the way for kidney dialysis. While the Nobel Prize represents

the pinnacle of achievement for scientists, it is more famous than its recipients

as the research that won the crown, like that of physicist Leon Lederman,

is usually beyond understanding. Biologist Paul Ehrlich, who made his work

understandable in a simple book, had the fame, appearing on The Johnny Carson

show more than two dozen times, but never won the Nobel Prize. Complicating

the matter, scientific breakthroughs such as in-vitro babies and cloned sheep

have given rise to public questions about the limits and morality of science

altogether. Ironically, moralists - philosophers, clergy, educators - have

seldom been seen as models of success.

Thomas Jefferson and Martin Luther King were deemed men of noble thought.

And in survey after survey, Americans report that teachers are the most influential

people in their lives. But rarely, however, do teachers mount the podium,

as in the case of Jaimé Escalante, whose riveting story in the movie "Stand

and Deliver" reminded us of their value. We have always admired individuals

of faith and virtue but we also seem to enjoy seeing them fall from grace.

And there have been a lot of tumbles. Jimmy Swaggart was involved with prostitutes

and Jim Bakker bilked his congregation. More dramatically, morality has changed

as strong opinions about homosexuality and abortion have led to divergent

moral views. As made obvious in his profile, reinforcing morality in order

to renew relationships and leadership is what Promise Keeper founder Bill

McCartney seeks to achieve. President Emeritus of Notre Dame and recipient

of the Medal of Freedom, Father Theodore Hesburgh, seeks even more. He wants

all humanity to be part of our relationships and leadership to become a synonym

for service that makes a difference in other's lives.

Historically, success was characterized by individual achievement that resulted

in a better America. But during the 20th Century, with the rise of mass communications,

the traditional meaning of success faded into history and Americans redefined

success in terms of notoriety. It was the media that helped make Joe Lewis,

George Gershwin, Mary Pickford, and Babe Ruth larger than life in an earlier

era and it is the media that have enshrined sport and entertainment stars

the global models of success today. Largely the result of film and television,

actors who portray notable moments in history have become more celebrated

than those who originally created them, and hitting a home run or a high C

offers a whole new meaning to notable. From Madonna to Michael Jordan, success

has come to be defined by momentary triumph in an illusionary world. As with

our notions about appropriate behavior, our notions about noteworthy achievement

are gradually adapting to the mass consensus coaxed out by media and marketing.

The result is that extraordinary achievement and success are now most frequently

defined by the accomplishments of those in sports and entertainment. The passion

for sports is extremely complicated because there is no one reason why it

exists. It is part spectacle and part religion. But many argue that sport

is one of the rare places where success and failure are measured against objective

standards, where excellence is the filter for achievement, where will and

hard work loom as standards. Such are clearly the virtues Hall of Fame football

coach Bill Walsh and Hall of Fame baseball manager Sparky Anderson advocated

for their teams and use to live their lives. And we appreciate that because

we live in a world where there is little objectivity. In other occupations,

success can be the result of circumstance, the achievers knew the right people

or they were born into it.

In sport, there is no other way but to combine talent with the passion of

Olympic ice hockey hero Mike Eruzione, the commitment of swimmer John Naber,

the work ethic of two-time American League Batting Champion Edgar Martinez,

the determination of Olympic gymnast Kathy Johnson-Clarke, the tenacity of

six-time Ironman Champion Mark Allen. Since most people do not have great

talent, watching sports lets them at least identify with success vicariously.

From the grandstands, fans are often more captivated by the athlete's intense

and often entertaining personality than by the performance. And along with

talent, today's athletes possess a charisma that few others can match. America's

Cup captain Dawn Riley and retired Boston Celtics basketball coach Red Auerbach

have it in spades, ultra distance athlete and TV commentator Diana Nyad, and

the best doubles player in tennis history Pam Shriver have it hearts, literally

and figuratively. But in contemporary American society, the epitome of success

is not the All-Star but the entertainment star. Movies have enormous power

over people. They enable people to escape safely from their reality. In the

1920s, an industry arose to bring good stories and intriguing people to the

silver screen. Award-winning cinematographer Ken Burns talks about the rigor

it takes to become one of the best at the craft. In the late 1940s, another

industry arose to bring those stories home and make their stars a part of

every household. Television became the nation's electronic campfire. In movies,

the audience could live out the dreams of what and where they would like to

be. In television, viewers found a mirror to their own worlds and found themselves

as heroes. Real world television star, Judge Mills Lane, minces few words

in telling you how to reach for your dreams in real life. Former fantasy world

television star and model, Rebekka Armstrong, does likewise telling you what

can happen when they are the wrong dreams. In part because of television,

all the arts are alive and well in America. Novelist Chaim Potok, choreographer

Mark Morris, and saxophonist Don Lanphere explain their path to the top of

those careers. Classical music, the performance medium with a list of achievers

that spans more centuries and more continents than any other medium, is also

flourishing, enabling Oregon Symphony maestro James DePreist and former St.

Paul Chamber Orchestra musical director Hugh Wolff, to stand on the podium

of success while working in two of America's smaller towns.

And despite the fact that only five percent of the public has any encounter

with classical music, recordings included, mass communications has helped

violinist Hilary Hahn, pianist Vladimir Feltsman, and cellist Lynn Harrell

to acquire stardom from a public that often knows little about the music they

play. Even opera has seen a renaissance in America substantially due to the

global broadcast of the Three Tenors concerts that catapulted Pavarotti, Carreras,

and Domingo from extraordinary voices appreciated by an elite niche to superstars.

And despite its highbrow reputation, opera does not require an intellectual

appreciation. It has visuals, energy, words, and music that are now packaged

and sold as entertainment instead of culture, making it an occasion for everyone.

Singer Frederica von Stade, talks about the magical moments of opera and its

relationship to her life. If the magic is in the visuals, energy, text and

music, then there are no greater magicians than rock musicians. And it is

they who are America's elite. No athlete, actor, or artist enjoys the adoration

of so many people.

Their celebrity is worldwide. Their achievement is built on passion. For some

it is intellectual, like the lyrics of Bob Dylan. For others it is emotional,

like a Janis Joplin wail. They are also the voices of freedom. Some of it

is sexual but some of it is political. When the Berlin Wall was falling down

and Eastern Europe was changing, teens there were inspired by rock messages

of hope. The essence of the message, the genre, and success within it are

the subjects of the Roger McGwinn profile, founder and lead singer for what

may arguably be America's first supergroup, the Byrds. While on first glance

sport and entertainment may appear to be strange bedfellows, they are far

more compatible than you think. Both suspend time. Both involve the unexpected.

Both are powerful emotional and social experiences where you are surrounded

by people sharing the same hopes, dreams, and champions.

Through sport and entertainment, individuals can get beyond their daily humdrum

existences and escape into another world. And when everything works, it really

is magic, and they talk about the performance for the rest of their lives.

These are exceptionally good times for sport and entertainment. In a world

without war and bolstered by a vibrant global economy, mass communications

delivers, for the first time in history, sports and entertainment twenty-four

hours a day, seven days a week, every day of the year, making us constant

and intimate spectators to the rich and famous. It really is no wonder Americans

believe that recognition is essential for success. And the data supports the

concept. Among the leading uses of discretionary income, Americans take lessons,

attend seminars, and hire personal trainers to be like those they deem successful.

Fascinated by those who have it, they purchase tickets to events and seek

autographs, take photos, and line highways to wave and to touch and compensate

for their perceived ordinariness. As a result, Americans cannot separate success

from notoriety, extraordinary accomplishment from extraordinary people, and

achieving great things from living great lives. That brings us back to the

three questions. Why do some people make it while others do not? I think you

will find in the profiles that a single answer to achievement is a myth. Yet,

I think you will also find that certain personality traits and personal needs

characterize achieving individuals and influence their ways of pursuing their

goals and responding to the opportunities and challenges en route. Is it worth

it when you get there?

I think the profiles will suggest that there are some heavy costs as well

as some surprising benefits to a life devoted to achieving. As to what is

success after all? That is a tough one. But, I hope through the profiles you

will come to understand the energizing, if often troubled, closing decades

of the 20th Century and at least differentiate success from stardom. In doing

so, you will have found the heart of success. But more of that a bit later.

Let's take a look at success through the eyes of those who seem to have it.

Excerpt from Chapter Two, It Takes Absolute Will

Karen Thorndike, First American Woman to Sail Around the World via the Great

Capes

Karen Thorndike completed her 33,000 miles sail around the world on August

18, 1998 when she returned to San Diego two years and fourteen days after

she began on August 4, 1996. When Thorndike docked, she became the first American

woman to circumnavigate the world alone in open ocean around the five Great

Capes: Cape Horn (South America), Cape of Good Hope (South Africa), Cape Leeuwin

(Australia), South East Cape (Tasmania), and Southwest Cape (New Zealand).

While there have been six other women to sail around the world, at age 56,

Thorndike is the oldest ever to accomplish the feat. "What I did would not

be considered great by everyone," Thorndike says without a hint of defensiveness,

"but it was for me because it required reaching beyond my limits. It was the

hardest thing I've ever done. I had to put every bit of my financial and emotional

resources, and all of my energy, toward it to accomplish it. It proved to

me that you can do anything you want to do if you just set your mind to it."

Storm damage to her 36-foot yacht Amelia, unseasonably bad weather, medical

problems, and moments of despair threatened to scuttle her 10-year dream.

During the most difficult part of her odyssey, Thorndike did not see land

for more than three months sailing from Mar del Plata, Argentina, to Hobart,

Tasmania. "There were some really low times in the Indian Ocean," she admits,

pausing briefly to reflect and then adding tongue-in-cheek, "but I wasn't

close enough to land to give up."

Isolated from everything, Thorndike endured relentless gales day after day

after day. Ironically, off the Cape of Good Hope, she was hit with near hurricane-force

winds and had to fight at the helm for 12 exhausting hours. And the worst

weather was yet to come. As Thorndike approached New Zealand's Southwest Cape,

the last of the five, the wind howled through the rigging at well over 65

knots producing seas with 40 to 50 feet swells. In retrospect, Thorndike got

what she had asked for. "I wanted to do one enormous, huge, very difficult

adventure in my life. I wanted to test everything: emotionally, physically,

spiritually, mentally; everything. I wanted to see just how far I could go."

Most people do not sit in their living room and fabricate a way to push the

edge of their psychic envelope. Most people sit in their living room because

it is comfortable. Thorndike was in that space. With commercial real estate

holdings that were returning well on her investment, she was setup to be financially

comfortable for life. In one gigantic moment, she spent all of it. "I could

always come back and go to work, find a little comfortable niche somehow,"

Thorndike offers comfortably in retrospect. "Maybe I wouldn't have a new BMW

or the most beautiful clothes, but I could always come back and make something

happen again. I couldn't always do this trip. The physical and emotional aspects,

the energy it required would not always be there."

Thorndike sold her holdings and when the transaction collapsed two months

before she was to depart and it appeared she would not be able to attempt

the voyage, she panicked. "Not being able to try was worse than trying and

failing because you cannot fail if you try to do something. That is not the

failure. The only failure is in not trying." In the United States, sailing

is not a sport that wins much public acclaim. There are ostensibly no sailors

benefiting from product endorsements and televised ads. In Britain, New Zealand,

Australia, and France, homes of the other women who have circumnavigated the

globe, more money is available and sailors even enjoy some fame. Thorndike

did not launch her boat for notoriety. "I love sailing. That was the big factor,"

Thorndike explains. "I really, truly feel at peace when I'm out in the ocean.

And it's a complicated activity, to handle the boat, navigate, take care of

the problems that arise. I had sailed for a long time before I even thought

about doing this and it's been ten years more since then before I tried. It

took that long to feel that I had the skills to do all the right things."

It truly did take Thorndike a long time to learn how to sail. She did not

grow up with a tiller in her hand. Her family didn't sail. She had never been

on a boat until 20 years ago and then she fell in love with it.

"Anything I learned, I learned the hard way. It doesn't take talent to sail

around the world. It takes absolute will. So, I hoped that I might be respected

for having done it." Thorndike takes a sip from her cup of coffee and a healthy

bite from her muffin and jam. With no prompting whatsoever, she gives her

ideas full sail and sets the course for those who would listen. "I feel very

passionate about life and what's out there. It's an incredible world. More

and more people are losing their passion. They get on the freeway, lock themselves

in and time punch the clock of life. I want them to tear up their punch cards

and go do something." When Thorndike tied up in San Diego at the end of her

journey, she indeed had done something. In doing so, she also found something.

"When I stepped onto the dock, immediately I felt at peace. I had really accomplished

my goal on a very personal level. I always felt like I had to prove myself.

Now I don't have to prove anything to anybody. I'm done. Whether they like

it, appreciate it, think it's crazy, think it's weird. It doesn't matter.

I accomplished something." We should all have such peace about our lives.

Copyright (C) 2000 Dan Tripps All rights reserved.

Return to main page of Trans-Atlantic Publications